Rude Awakening

When the wind started in Lincoln, Nebraska, around 5 AM on the morning of Saturday, August 9th, Dr. Eric Hunt, like many others, quickly woke up. Stumbling to his feet and finding a window in his northeast Lincoln home, the professional climatologist tried to quickly determine the irritating early start to the day.

“It was a little more than a gust. I was like, what is going on?”

The dazed reaction would be a similar reaction to my waking to tornado sirens in Bellevue, about 40 miles to the east of Lincoln, an hour later. “Why am I hearing tornado sirens!”, my brain demanded. My confusion was not helped by the fact that Bellevue was south of the worst of the storm, I could see the rising sun to the southeast, and the sky was brightening for us, not darkening.

Dr. Hunt, an extension educator for the state of Nebraska with a focus on climate applications and agriculture, quickly realized that the forecast for scattered overnight thunderstorms had evolved into something much more significant. “It was loud.”

The wind came to Lincoln before most of the rain, with only one small shower sprinkling parts of Lincoln as the night winds gusted past 60 MPH. After about 20 minutes, as the wind continued to blow, the rain finally started.

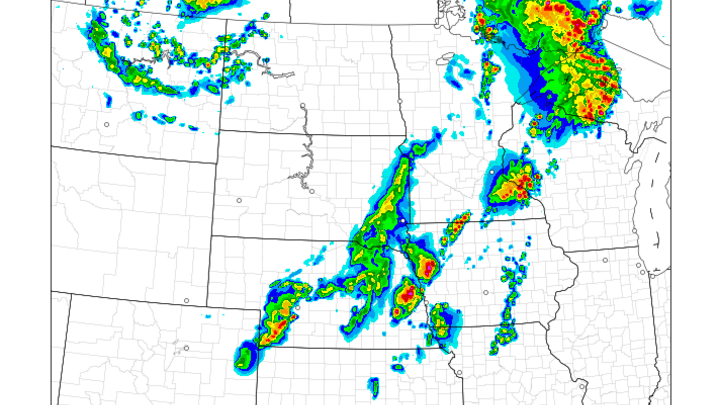

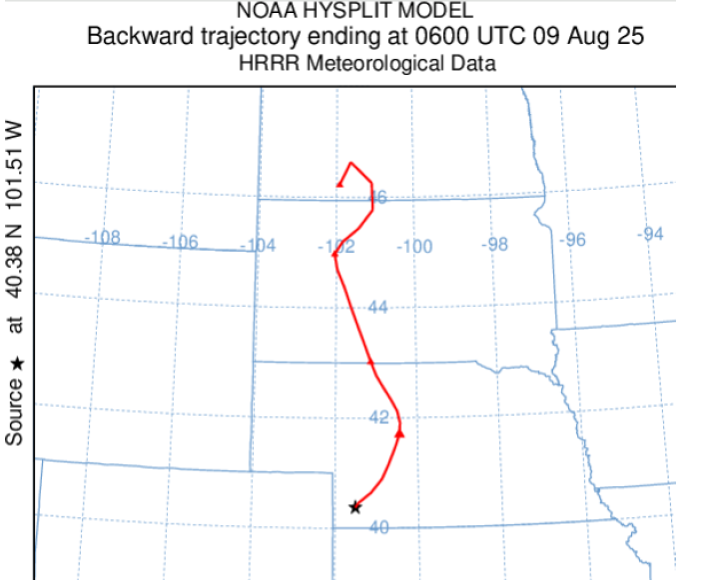

Severe thunderstorms were forecast in Nebraska on the evening of the 8th, but the focus of meteorologists was primarily on western Nebraska, from Valentine south towards McCook and west towards Chadron. Most of Nebraska was placed in a marginal risk for severe thunderstorms by the Storm Prediction Center – 1/5 on the numeric forecasting scale – and southeastern Nebraska was only mentioned for general thunderstorms (Figure 1):

Figure 1: 3 PM Storm Prediction Center Thunderstorm Forecast

Some overnight rain was possible in southeastern Nebraska, but for many in eastern Nebraska, the weekend was to be one last camping opportunity before school and sports schedules kicked into high gear. A little bit of rain was not going to stop anybody. However, when Dr. Hunt woke, “it looked like a hurricane outside.” Chairs were tossed around and limbs came down as winds approaching 75 MPH marched through the city. Though the rain was heavy and blinding in the wind, only .18” fell during the storm.

Where did this storm come from?

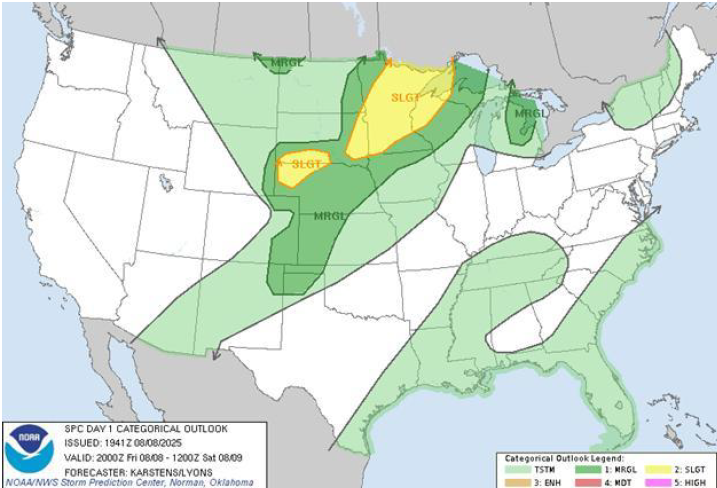

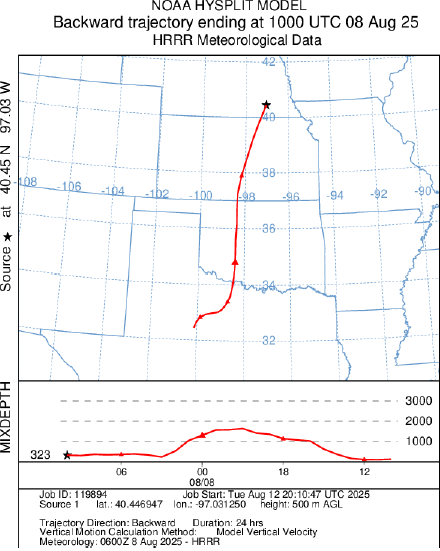

Thunderstorms did form as expected in southwestern Nebraska, near the Colorado border with 1” diameter hail reported northeast of Goodland, Kansas, at 10:43 MDT. Forming in northerly winds behind a surface frontal boundary, the atmosphere was still humid for the location, with late-evening dew points in the mid to upper 60s from North Platte south across the state line into northern Kansas. The source air for these thunderstorms was from the Dakotas, shown by the parcel trajectory map from the HYSPLIT model from NOAA’s Air Research Laboratory (Figure 2):

Figure 2: Parcel back-trajectory for southwestern Nebraska, 12 AM 9 August 2025

Though the surface dew points were high, the overall atmospheric profile remained seasonally dry for western Nebraska. This parcel trajectory was pulling air from an evening sounding in Rapid City (Figure 3) that indicated .83” of precipitable water. While about average for early August, we will see shortly that this storm will encounter much, much more humid, unstable air as it travels to the east and intensifies.

Figure 3: 6 PM MDT Rapid City atmospheric sounding

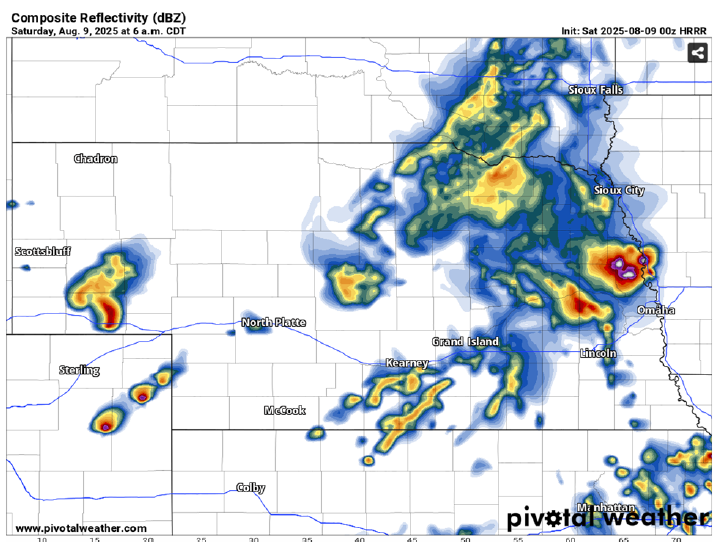

These thunderstorms diminished in intensity as they moved past McCook in southwestern Nebraska, and existing severe thunderstorm warnings were allowed to expire. Numerical guidance provided little guidance to suggest what was about to happen. The 7 PM run of the High Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model (Figure 4) latched on to the idea that one storm would march across the southern portion of the state, intensifying as it pushed east into increasingly humid and unstable air, moving past the Omaha area by 6 AM - a very accurate foretelling of what was to happen, with enough lead time to provide tangible value to users.

Figure 4: 7 PM CDT August 8 HRRR Model, Forecast Valid 6 AM CDT

The HRRR forecast did not have a lot of company with this solution from other models, however, nor had the HRRR given users much reason to trust its solutions without supporting evidence over the past several weeks. Skepticism abounded in forecast circles about this possibility.

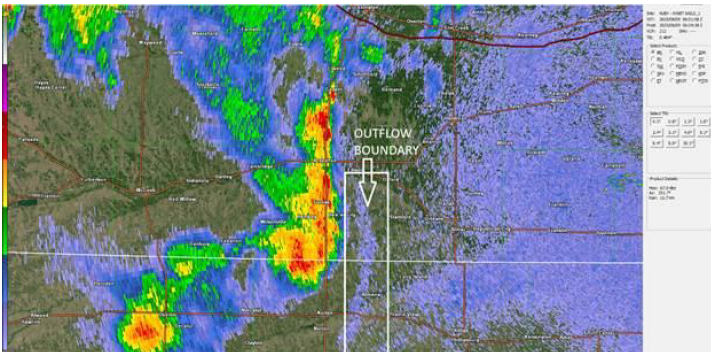

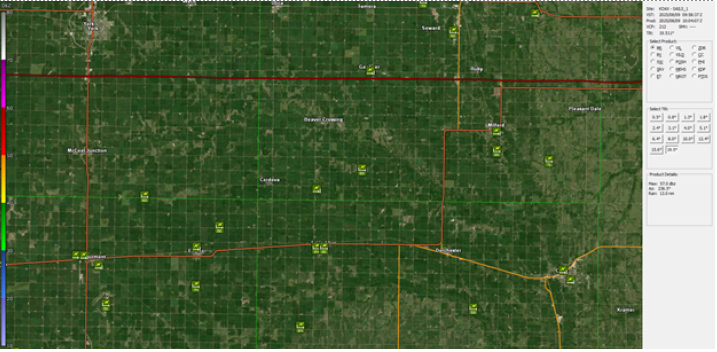

East of McCook around 1 AM CDT, near the town of Beaver City, the thunderstorm complex took on a different and more menacing appearance on radar. Multiple updraft cores appeared to be reinvigorated. An outflow boundary – indicating a rushing gust of cool air ahead of the storms - appeared to the east of what was becoming a solid line of thunderstorms (Figure 5), and for rural Nebraskans just north of the Kansas border, the night wind suddenly picked up amidst increasingly frequent flashes of lightning to the west:

Figure 5: 107 AM CDT Hastings Radar: Base Reflectivity

Evolving storm

Between 1:15 AM and 1:30 AM CDT, three different reports of winds near 50 MPH were reported east of Beaver City. At 1:50 AM, the National Weather Service in Hastings issued a severe thunderstorm warning for portions of south-central Nebraska, including the towns of Kearney, Holdrege, and Minden.

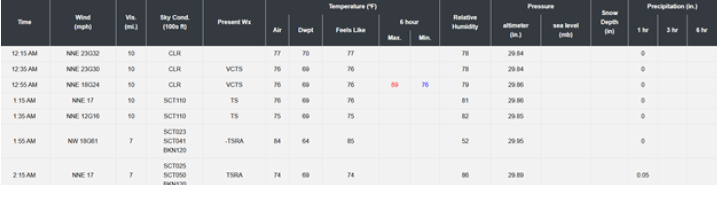

At 1:55 AM, 61 MPH winds were reported in Holdrege. Holdrege did not experience any cool air when this outflow boundary passed through town, instead experiencing a minor heat burst, the temperature rising to 83 degrees from 75 degrees. 20-minute observations from Holdrege are shown below (Figure 6), including the dew point dropping to 64 degrees, another sign that dry, descending air from decaying thunderstorms to the west had reached the ground:

Figure 6: 1 AM - 2:30 AM Observations at Brewster Field in Holdrege, Nebraska

Had the air been cooler, the threat of damaging winds downstream may still have existed, but the storm structure would have been very different, and a squall line would have been more difficult for large-scale atmospheric conditions to sustain – squall lines moving from west to east tend to have strong westerly winds aloft to help push them forward, and this atmosphere’s winds were largely south-southwesterly aloft. A bow echo would have tried to push farther north, with the mid-level winds aloft, away from the surface front, surface moisture, and atmospheric instability.

The southern updraft, closer to the warmest, most humid air, continued to grow about 20 miles south of Holdrege on radar at about the same time. At 2 AM, the storm that becomes such a problem for so much of southern and eastern Nebraska begins to ramp up over the towns of Ragan and Huntley, an area of the state that has suffered greatly from wind-driven hail in the past decade. Observations from the Smith Center station indicate that the thunderstorm remained in northerly flow at this time, but that southerly winds just above the surface – rich in humidity - were beginning to influence the storm, allowing for slow destabilization of the atmosphere ahead of the storm and promoting intensification.

Figure 7: 159 AM Hastings radar: Base Reflectivity

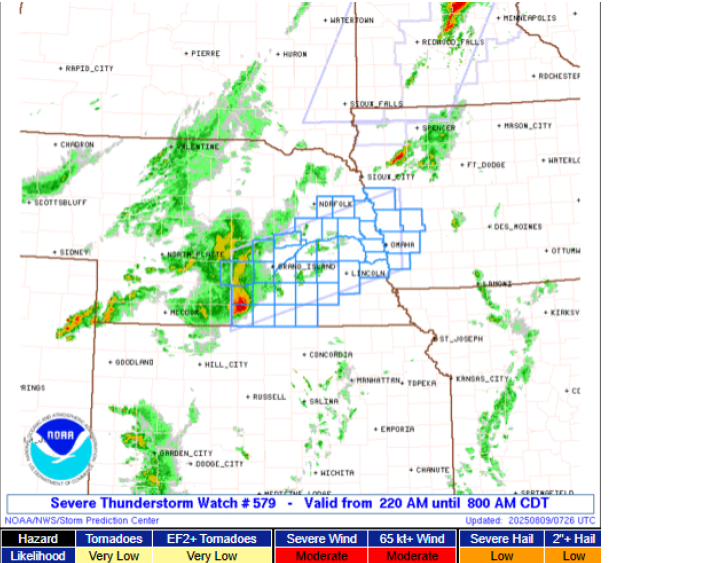

25 minutes after the wind gust report in Holdrege, the Storm Prediction Center grew concerned enough about the long-range threat of damaging winds that a severe thunderstorm watch (Figure 8) was issued for much of southern and southeastern Nebraska, though the text of the watch continued to underestimate the impact of the event, with only isolated gusts to 75 MPH mentioned in the text:

Figure 8: Severe Thunderstorm Watch #579

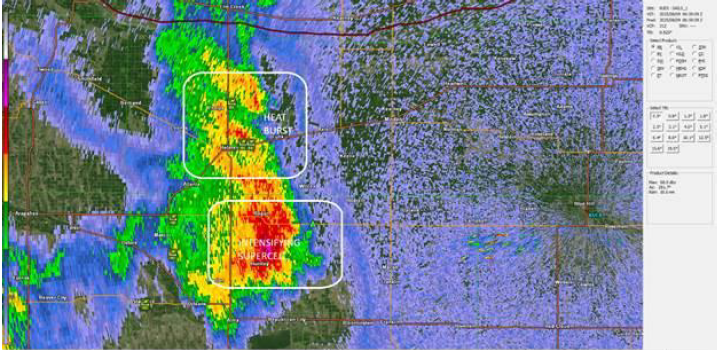

Becoming a supercell

The structure of the storm changes rapidly between 2 AM and 2:20 AM CDT over northern Franklin County. The little town of Hildreth - a town of 300 people located a few miles west of Highway 10 - is where the first signs of serious trouble emerge. “Lots of branches down”, comes the news from town. By the time the storm passes Upland, about 6 miles to the east, radar scans of the atmosphere above the surface indicate vigorous mid-level rotation – this storm has become a supercell.

Why does storm type matter? Supercells are thunderstorms that possess deep rotation throughout the core of the storm. This rotation allows warm updraft air to separate from falling rain, increasing the amount of fuel to the storm and extending the length of the storm’s life, sometimes by several hours. The size of the storm has also increased, now measuring more than 10 miles across on radar. It is not so easy for dry air to kill a larger storm. 15 miles east of Hildreth, the town of Bladen records a 70 MPH wind gust, and the conglomeration of updrafts begins to take on more of an appearance of one big rain-soaked wind machine:

Figure 9: 256 AM CDT Hastings radar - Base Reflectivity

East of the town of Hastings, the intensity of wind measurements and the severity of the reports both continued to increase. Surface map analysis at 2 AM CDT (Figure 10) indicates a frontal boundary very near to Hastings, with southerly winds and slightly warmer temperatures ahead of the front and northerly winds behind the boundary. The temperature at Beatrice had only fallen to 82 by 2 AM - the storm was moving into very warm air in addition to very humid air. The storm, previously traveling north of the boundary, finds the boundary in south central Nebraska, near Hastings:

Figure 10: 2 AM Surface Observations in Southern Nebraska

Path of destruction

The continued intensification and maintenance of the storm’s supercell structure owing to finding this boundary appears to have been almost immediate, and the storm would ride the boundary for the next several hours into western Iowa. A 75 MPH wind report came from Sutton, 20 miles to the east, and shortly after that, a 91 MPH wind report came from the town of Fairmont, just a few miles east of Sutton. Radar suggests that a brief tornado may have occurred in this area, but amidst the rain, the pitch black skies of the rainy night, and the surrounding similar damage, it is impossible to tell.

In Clay County in particular, several of the wind reports were accompanied by hail, a particularly nasty threat to mature crops. From Sutton through Lincoln (Figure 11), wind reports of 80 MPH were common, and the Lincoln airport gusted to 91 MPH as well. Many of these areas were hit hard by the mid-March blizzard, where winds to 70 MPH in blowing snow caused severe tree and power line damage.

Figure 11: Wind Reports across Clay and Fillmore Counties

Beyond Lincoln, damaging winds were nearly continuously reported across the Missouri River and through Missouri Valley, finally weakening near Carroll in western Iowa. This damage included a 78 MPH wind gust near Waterloo, an area still rebuilding from the tornado of April 26th, 2024, and an 87 MPH wind in Millard, hard hit by the July 31st storm.

Record moist air

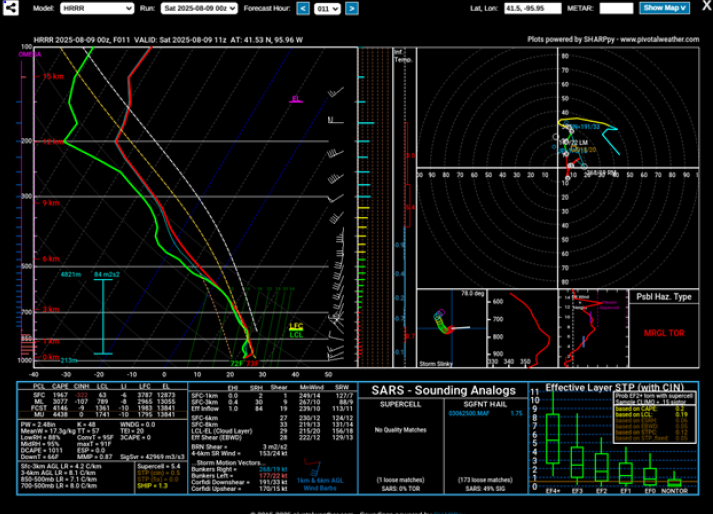

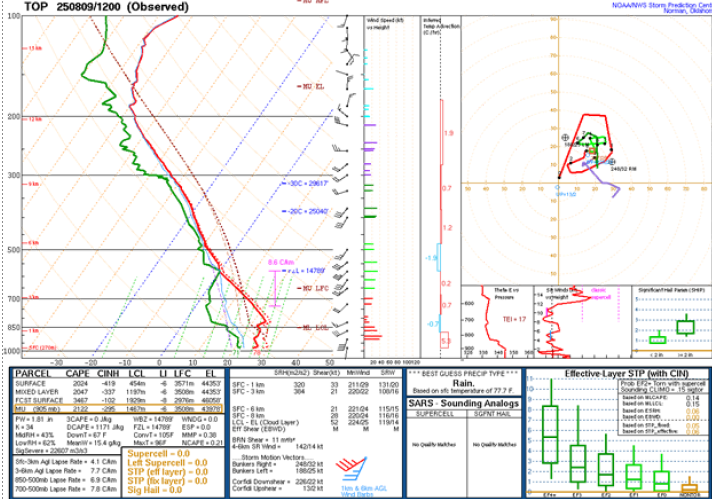

While the exact structure and tornado potential of the storm remained extremely confusing even in retrospective radar analysis, one thing meteorologists could say for certain was that the violent thunderstorm was feeding on extremely humid air to its south and east – a forecast sounding from the aforementioned HRRR model taken ahead of the thunderstorm valid at 6 AM (Figure 12) revealed an atmosphere with robust instability and near-historic levels of moisture:

Figure 12: HRRR Forecast sounding, Valid at 6 AM CDT, thunderstorm inflow

How unusual is 2.48” of precipitable water in eastern Nebraska? In the dataset provided by the Storm Prediction Center sounding climatology compiling data from balloons launched from the Omaha/Valley National Weather Service and its predecessors, the highest value ever recorded (Table 1) was 2.38”. For August 8th, the 90th percentile – the upper 10% of values recorded for that day – is a relatively miniscule by comparison 1.65”.

| Date | Precipitable Water |

| 6/24/85 | 2.38 |

| 7/15/10 | 2.37 |

| 7/4/10 | 2.37 |

| 8/1/66 | 2.36 |

| 7/16/11 | 2.34 |

| 8/7/07 | 2.33 |

| 7/16/11 | 2.32 |

| 8/3/10 | 2.32 |

| 7/22/10 | 2.31 |

| 8/2/97 | 2.30 |

Table 1: Top 10 Historical precipitable water values(inches) from Omaha soundings

The air that was now fueling the monstrous storm was all humid, southerly moisture, and HRRR-based parcel trajectory (Figure 14) shown here also indicated that the mixed layer depth was only 323 meters ahead of the storm. In addition, as the storm rode along the frontal boundary, the easterly surface winds along and north of the boundary continued to promote rotation in the storm, allowing for the storm to maintain its supercellular characteristics for hours.

Figure 14: Parcel trajectory for southeastern Nebraska, valid at 5 AM CDT

Where the original storms near McCook were pulling drier air from Rapid City, the storm now is pulling very humid air from northern Kansas, with the morning sounding from Topeka (Figure 15) indicating 1.81” of precipitable water:

Figure 15: 7 AM August 9th Topeka KS Sounding

When the storm reached the frontal boundary near Hastings, it gained another weapon in its means of destruction - the storm encountered an atmosphere with less stability near the ground. Downdraft winds did not have to fight to reach the surface - stability that had been acting as a bit of a parachute in southwestern Nebraska to limit the strength of the wind reaching the surface was no longer in place, giving the downdrafts less resistance and increasing the intensity of ground-level winds.

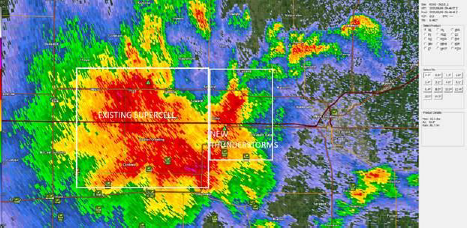

New thunderstorms were also consistently forming along small outflow boundaries ahead of the storm, and the ingestion of these cells into the main complex tended to coincide with significant damage, most notably near the town of Seward (Figure 16), west of Lincoln:

Figure 16: 446 AM CDT Omaha radar: Base Reflectivity

The Aftermath

In Lincoln, lights flickered for Dr. Hunt and his wife, and then the power went out for good, the outage lasting for 7 hours, “the longest we’ve been without power”, ending just after noon. “Our third power outage in 13 months”, Dr. Hunt recalled, noting similarities and differences to the severe thunderstorm from July 31st of 2024. “I don’t know if I’ve seen damage [in Lincoln] to this extent”, he continued, discussing how though the July 31st storm impacted Lincoln. Plenty of branches and roof shingles needed to be cleaned up that evening, but the worst damage was east of town as the storm continued to intensify into the Omaha metropolitan area. As of early Saturday afternoon, 28,000 Lancaster County buildings were without power, compared to 7,000 after the storm in July 2024. This time, garages were damaged beyond repair. Vehicles were totaled.

Figures 17-18: Wind damage in central Lincoln

Nebraskans did what Nebraskans do, though – they went to work. “The neighbors had a better chainsaw”, he mused. Besides the desire to help, many Lincolnites were eager to get their big toys out to play.

By the mid-afternoon, the marks of the storm were beginning to fade as one truck after another made their way to city locations designated as pickup locations for branches and limbs. Had the event taken place on a workday or during college football season, the cleanup might have taken a day or two longer. On a sunny Saturday morning – the clouds far to the east by noon – neighbors helped neighbors, and one limb at a time, Lincoln put itself back together.

With another active night promised for southeastern Nebraska on Saturday – winds to 90 MPH would impact areas near Superior, southwest of Lincoln and only a handful of miles south of Saturday morning’s damage path, and rainfall totals in the 3-5” range would be reported throughout southern and southeastern Nebraska as well – Dr. Hunt’s attention turned towards what the weekend’s active weather meant for agriculture and the entire summer.

For areas south and west of Lincoln along Highway 6, the damage of a rainy summer would be readily apparent at sunrise. The strongest winds measured exceeded 90 MPH, and in an area south of York, the high winds were accompanied by hail. Cornstalks stripped of leaves and fruit. Beans blown flat. Grain bins caved in, such as this one in northeastern Fillmore County:

Figure 19: Collapsed grain bin near Geneva

A challenging growing season and upcoming harvest months in the making, abruptly ended in seconds. For many farmers in the area, the loss was eerily reminiscent of the June 14th, 2022 storm, another crop season obliterated in seconds by atmospheric ice missiles. Lifeless stalks are the only remaining product of months of hard work, sweat, joy, pride, and tears.

The storm took more than agriculture. At Two River State Park west of Omaha, a Cottonwood tree falling on a vehicle killed a woman and seriously injured her husband after the couple left their tent, seeking sturdier shelter from the rain and wind.